Lactobacillus acidophilus: History, Natural Habitats, and Health Benefits of This Probiotic Powerhouse

- NPSelection

- Aug 8, 2025

- 4 min read

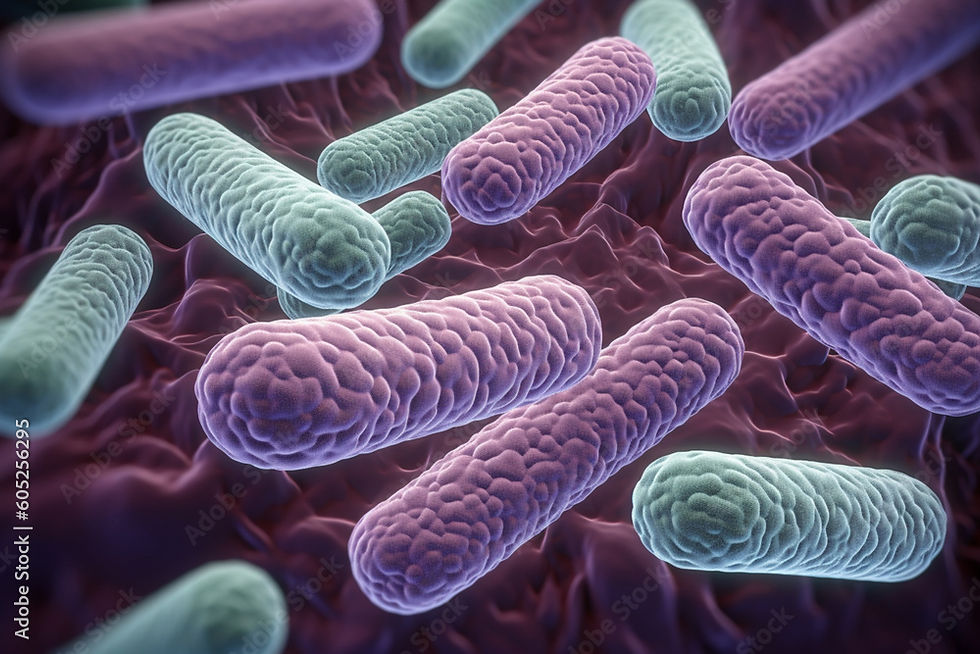

Lactobacillus acidophilus (L. acidophilus) is one of the best-known and most widely used probiotic bacteria, valued for its ability to support digestive, immune, and vaginal health. Found in humans, animals, and fermented foods worldwide, this “acid-loving” bacterium has a fascinating story and continues to play a crucial role in our well-being.

History and Discovery of Lactobacillus acidophilus

Lactobacillus acidophilus was first discovered in 1900 by American microbiologist Albert Francis Blakeslee, who isolated it from the human intestine. He noted its preference for acidic environments — earning it the name “acidophilus,” or acid-loving.

Around the same time, Nobel Prize winner Élie Metchnikoff was publicising the idea that lactic acid bacteria from yoghurt and fermented milk could help extend lifespan and improve gut health. Although Metchnikoff focused on Lactobacillus bulgaricus, his ideas paved the way for L. acidophilus and other lactobacilli to be recognised as health-promoting microbes.

By the 1950s, L. acidophilus was being added to milk products and sold as supplements, a trend that continues to this day.

Global Presence and Geographical Spread

What makes L. acidophilus remarkable is its global reach. It has been isolated from healthy people and animals in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia — evidence of its long evolutionary relationship with mammals.

However, factors such as modern diets, high antibiotic use, and stress have reduced the natural levels of L. acidophilus in many people. This is why probiotic supplements and probiotic-rich foods are now recommended for many to maintain balance in their microbiome.

Where Does Lactobacillus acidophilus Live?

In nature, Lactobacillus acidophilus is found in the following habitats:

Human intestines — especially the small intestine and colon, which help regulate gut flora.

Vaginal microbiome — helps maintain low pH and suppresses harmful microbes.

Animal digestive tracts are present in mammals like cattle, pigs, and poultry.

Fermented dairy products — present naturally or added as a starter in yoghurts, kefirs, and acidophilus milk.

💡 Did You Know?

Lactobacillus acidophilus is one of the few bacteria that can survive the highly acidic environment of the human stomach, thanks to its name, which means “acid-loving.”

It’s one of the earliest probiotics ever used in commercial products, with “acidophilus milk” first sold in the United States as early as the 1920s.

The bacteria produce lactic acid as they digest sugars, which helps lower the pH of their surroundings, making it harder for harmful bacteria to grow.

Despite its long association with humans, studies show that only about 10–20% of people in modern, industrialised countries still carry L. acidophilus naturally in significant numbers, primarily due to diet and antibiotic use.

In addition to its benefits for human health, L. acidophilus is also utilised in animal nutrition, helping to maintain gut health in livestock and poultry.

Does Lactobacillus acidophilus Permanently Colonise the Gut?

In healthy adults, L. acidophilus — even when taken in high doses — typically does not establish long-term colonisation of the gut microbiome.

Evidence:

In a controlled trial, Frese et al. (2012) found that supplementation with L. acidophilus increased its abundance during use; however, levels declined rapidly once supplementation was stopped.

Similar findings were reported by Maldonado-Gómez et al. (2016), who showed that introduced probiotics rarely persisted in stool samples beyond a few weeks after cessation.

This is because:

The gut microbiome is already densely populated and highly competitive.

L. acidophilus is more adapted for mucosal surfaces and transient activity than for durable colonisation of the adult gut ecosystem.

Thus, it is considered a transient coloniser: it passes through and interacts with the gut microbiota, exerting beneficial effects without permanently integrating into the host microbiome.

Why Temporary Colonisation Still Matters

Even though L. acidophilus does not persist indefinitely; its temporary presence has measurable and clinically meaningful effects:

Digestive Benefits

Restores microbial balance during and after antibiotic treatment (Ouwehand et al., 2002).

Reduces the incidence and duration of diarrhea, including traveler’s diarrhea and rotavirus-associated diarrhea in children (FAO/WHO, 2002).

Immune Modulation

Stimulates mucosal immunity by interacting with dendritic and epithelial cells (Sanders, 2008).

It may help reduce inflammatory responses in conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome.

Competitive Exclusion of Pathogens

Produces lactic acid, lowering gut pH and making it harder for pathogens like Salmonella, Clostridium difficile, and E. coli to thrive.

Produces bacteriocins and hydrogen peroxide, which possess antimicrobial properties.

Vaginal and Urogenital Health

Supports the vaginal microbiota by temporarily colonizing and producing lactic acid, which suppresses overgrowth of Candida and Gardnerella species.

In essence, its transient colonisation is enough to shift the microbial balance toward a healthier state.

Conclusion

While Lactobacillus acidophilus does not typically establish permanent residence in the adult gut, it remains a valuable probiotic because its temporary colonisation improves microbiome function, suppresses harmful bacteria, and modulates the immune system. This underlines the importance of regular or sustained consumption of probiotics in individuals who benefit from them.

Final Thoughts

From its discovery in 1900 to its modern use in supplements and functional foods, Lactobacillus acidophilus has proven itself as a key player in human health. Whether you’re looking to improve digestion, support your immune system, or maintain vaginal health, this humble probiotic continues to deliver.

References

Ouwehand AC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. (2002). Probiotics: an overview of beneficial effects. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 82(1–4), 279–289. DOI: 10.1023/A:1020620607611

FAO/WHO. (2002). Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and World Health Organisation. Link

Sanders ME. (2008). Probiotics: definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 46(Supplement_2), S58–S61. DOI: 10.1086/523341

NIH – National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Probiotics: What You Need to Know. Link

Frese, S.A., Hutkins, R.W., Walter, J. (2012). Establishment of a human milk oligosaccharide-utilizing gut microbiota in germ-free mice and colonization by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(5), 1602–1609.

Maldonado-Gómez, M.X. et al. (2016). Stable engraftment of Bifidobacterium longum in the human gut depends on individualized features of the resident microbiome. Cell Host & Microbe, 20(4), 515–526.

Comments